Just how is it that a ceiling fan, an appliance designed to aid in relaxation and comfort by cooling the home, can seemingly manifest the very essence of evil and foreboding?

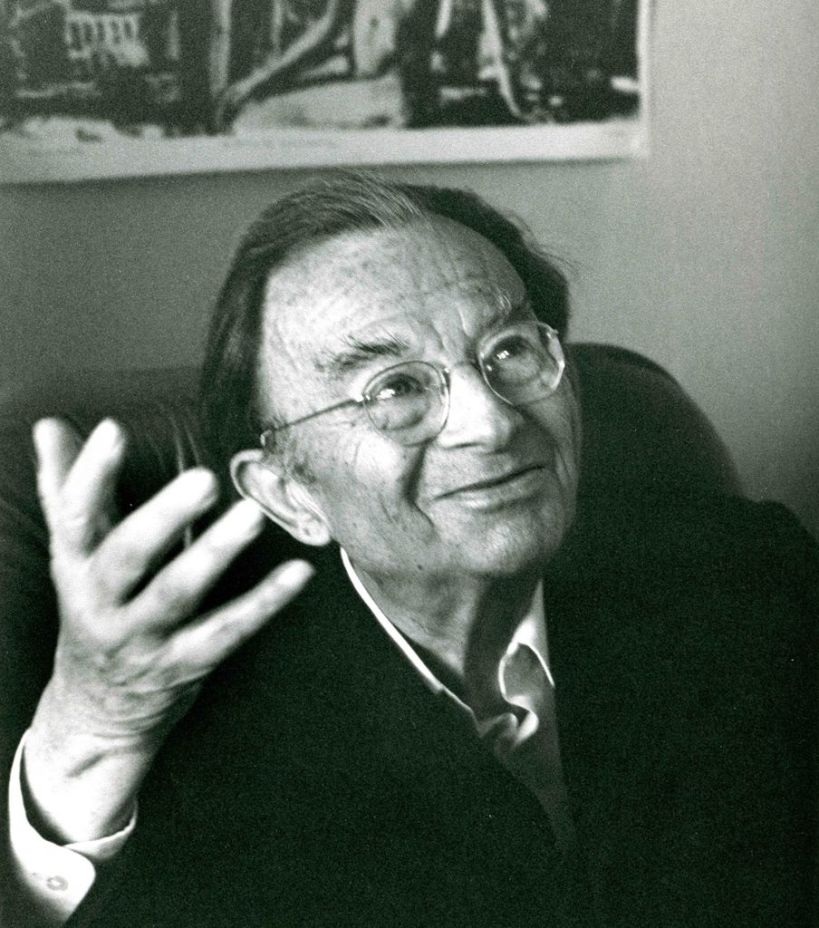

I suggest that through a brief survey of object-relations theories in psychoanalysis we can find some compelling answers to this question. To fully grasp the argument I’m about to make we must first have some acquaintance with Melanie Klein’s important contributions to our understanding of schizoid mechanisms (schizoid as in to ‘split’). In Klein’s formulation, beginning in early childhood, unbearable affects are defended against by the fracturing experience into what she called ‘part-objects’. These are typically split representations of other people, usually as all good or all bad, idealized or devalued, a source of pleasure or of agony. Readers familiar with Hegel or Derrida will instantly recognize this as binary thinking in need of dialectical synthesis and transcendence.

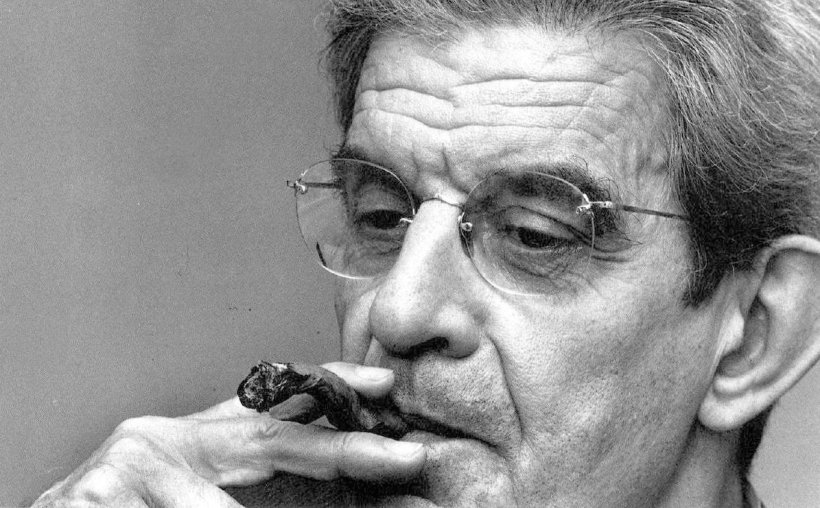

However, the trouble is the complex and disappointing nature of reality can often be too much to bear even for those equipped with a rudimentary education in dialectics. By this I simply mean that some affects are perceived as so sinister and threatening that they cannot be accommodated by the ego-self and are liable to become split off with great fervour. For Wilfred Bion, a protege of Klein, this situation differs from the part objects she described in a few fundamental ways. For Bion, this more extreme variety of splitting is central to his theory of psychosis wherein those psychic structures responsible for keeping the subject in touch with reality and morality are violently attacked and externalized.

Although they are in this way obscured, these elements do not simply vanish, rather they are projected out into the external world. This results in the uncanny state of mind wherein the subject may perceive inanimate objects as carrying certain alienated elements of his or her own psychic structure.

“If the piece of personality is concerned with sight, the gramophone when played is felt to be watching the patient; if with hearing, then the gramophone when played is felt to be listening to the patient. The object, angered by being engulfed, swells up, so to speak, and suffuses and controls the piece of personality that engulfs it: to that extent the particle of personality has become a thing … The consequences for the patient are now that he moves, not in a world of dreams, but in a world of objects which are ordinarily the furniture of dreams” (Bion, Differentiation of the psychotic from the non-psychotic, 1957, p. 51).

“We are like the dreamer who dreams and then lives inside the dream” – Lines delivered within a dream sequence by Monica Bellucci playing herself during an episode of Twin Peaks: The Return.

In Lynch’s Twin Peaks the notorious ceiling fan which apparently comes to life every time Laura Palmer suffers incestuous abuse at the hands of her father Leland can be viewed from this perspective as a bizarre object which contains a plethora of projections of family pathology and casts a very dark shadow. The suggestion that the fan’s electrical current is the medium by which the evil spirit BOB possesses Leland during his acts of abuse, and his use of it’s blank noise for the purpose of secrecy, shows it to be a vessel for the affects generated in the conflict between the lecherous desires of his id and the moral masochism of his super-ego.